How the Femoral Head Sets the Stage for Healthy Movement: Anatomy, Alignment, and Rotation

![]() The femoral head is a key player in one of the most dynamic and misunderstood joints in the human body—the hip. Nestled inside the acetabulum of the pelvis, this ball-shaped structure enables an incredible range of motion while supporting the full weight of the body during every step we take. But how well the femoral head is seated in its socket determines everything from posture to joint health to ease of walking.

The femoral head is a key player in one of the most dynamic and misunderstood joints in the human body—the hip. Nestled inside the acetabulum of the pelvis, this ball-shaped structure enables an incredible range of motion while supporting the full weight of the body during every step we take. But how well the femoral head is seated in its socket determines everything from posture to joint health to ease of walking.

Before I injured my knees and underwent three knee surgeries, I was guilty of walking like the picture above. Leaning backward with my feet turned out and initiating every step from the lower leg instead of the core.

In other words, my femurs were rarely, if ever, well aligned in the hip socket.

Let’s explore the anatomy of the femoral head, its relationship with the pelvis, how internal and external rotation work, and why many people unconsciously move in ways that keep this joint misaligned.

Anatomy of the Pelvis and Femur

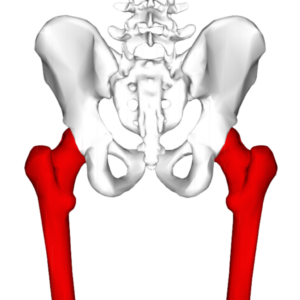

The pelvis consists of three bones: the ilium, ischium, and pubis. These converge to form the acetabulum, a deep, curved socket designed to house the femoral head. The pelvis doesn’t just sit still—it tilts, shifts, and rotates with every step, playing a vital role in the mechanics of walking and standing.

The femur, the largest bone in the body, extends from the hip to the knee. Its upper end forms the femoral head, which articulates with the acetabulum. Together, they create a ball-and-socket joint—one of the most mobile joint types in the body, allowing movement in multiple planes: flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and crucially, internal and external rotation.

This wide range of motion is remarkable but must be precisely controlled.

The Role of the Iliofemoral Ligament and Surrounding Muscles

The iliofemoral ligament is one of the strongest ligaments in the human body. It attaches from the pelvis to the femur and limits excessive hip extension and external rotation. When we stand upright, this ligament helps prevent the torso from falling backward and keeps the femoral head centered in the socket.

Several muscles also contribute to the dynamic control of the hip, including:

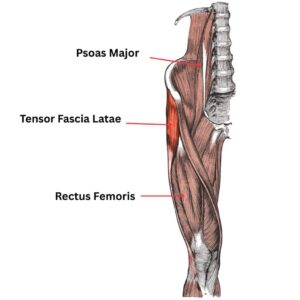

- Rectus femoris: A hip flexor and knee extensor.

- Tensor fascia latae (TFL): A small muscle on the outside of the hip involved in flexion, abduction, and internal rotation.

- Psoas major (my favorite muscle): A deep core muscle that originates from the lumbar spine and inserts into the lesser trochanter of the femur. The psoas is a powerful hip flexor and one of the few muscles that directly links the spine to the femur. It plays a crucial role in maintaining optimal alignment of the femoral head in the socket, especially during walking and standing.

But the stars of stabilization are the deep hip stabilizers, which include:

- Piriformis

- Gemellus superior and inferior

- Obturator internus and externus

- Quadratus femoris

These small muscles don’t generate large movements, but they provide precise, moment-to-moment stability of the femoral head within the acetabulum—especially during weight shifts and rotation.

The Pelvis and Femoral Head in Motion

With every step, the pelvis tilts and rotates. During midstance—the point in the gait cycle when one leg supports the body and the foot is flat on the ground—the femoral head should be in neutral alignment within the acetabulum. This is when weight-bearing is most efficient and least stressful on the joint.

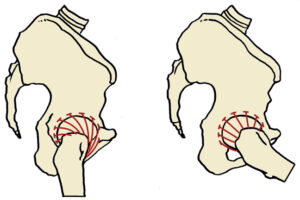

However, many people habitually sink their thighs forward when standing and walking. This postural misalignment causes the femurs to fall into external rotation, pushing the femoral head slightly forward and out of alignment. As a result, internal rotation becomes restricted.

Here’s the interesting part: in this chronically externally rotated posture, what feels like a “neutral” leg is actually slightly internally rotated in relation to the pelvis. So, when we walk, we’re often moving from a baseline of insufficient internal rotation and further into excessive external rotation—never truly passing through real neutral.

The Problem with Never Centering the Femoral Head

If the femoral head never fully seats into the acetabulum, the joint operates at a mechanical disadvantage. Over time, this leads to uneven wear, joint stress, compensatory movement patterns, and chronic tightness in surrounding muscles like the TFL, rectus femoris, and psoas.

When the deep stabilizers aren’t doing their job, and when the psoas is either too tight or too weak, the iliofemoral ligament becomes over-relied upon for passive stability. The result? A rigid, locked-up hip that lacks rotational freedom—especially internal rotation, one of the most commonly restricted movements in modern bodies.

Restoring Healthy Hip Function

The goal is to realign the femoral head in the socket by retraining both posture and movement:

- Stand with your thighs stacked under your pelvis, not forward of it.

- Restore internal rotation capacity through targeted mobility and strengthening.

- Activate the deep hip stabilizers, especially in functional positions like single-leg stance.

- Balance the psoas, ensuring it is neither short and grippy nor weak and inactive.

When we walk with this alignment, the pelvis and femur cooperate fluidly. The femoral head stays centered, the joint functions efficiently, and we gain back the natural rhythm and ease of movement our bodies are designed for.

By paying attention to how the femoral head interacts with the pelvis—and by retraining how we stand, stabilize, and walk—we can unlock a powerful shift in hip health, mobility, and whole-body alignment.